Researching Through Gaps: Furniture, Atmosphere and Architectural Weight

This phase focused on building the foundations for a viable modular joining system. Rather than producing work immediately, I concentrated on research — archival, contextual and material — to ground what would follow.

My original plan was to work directly inside the High Wycombe Furniture Archive, studying technical drawings and production documents firsthand. That plan collapsed quickly. The archive was mid-restructuring, access limited. Waiting would have stalled the project.

So I shifted online. The constraint shaped the research rather than stopping it.

Working With What Exists

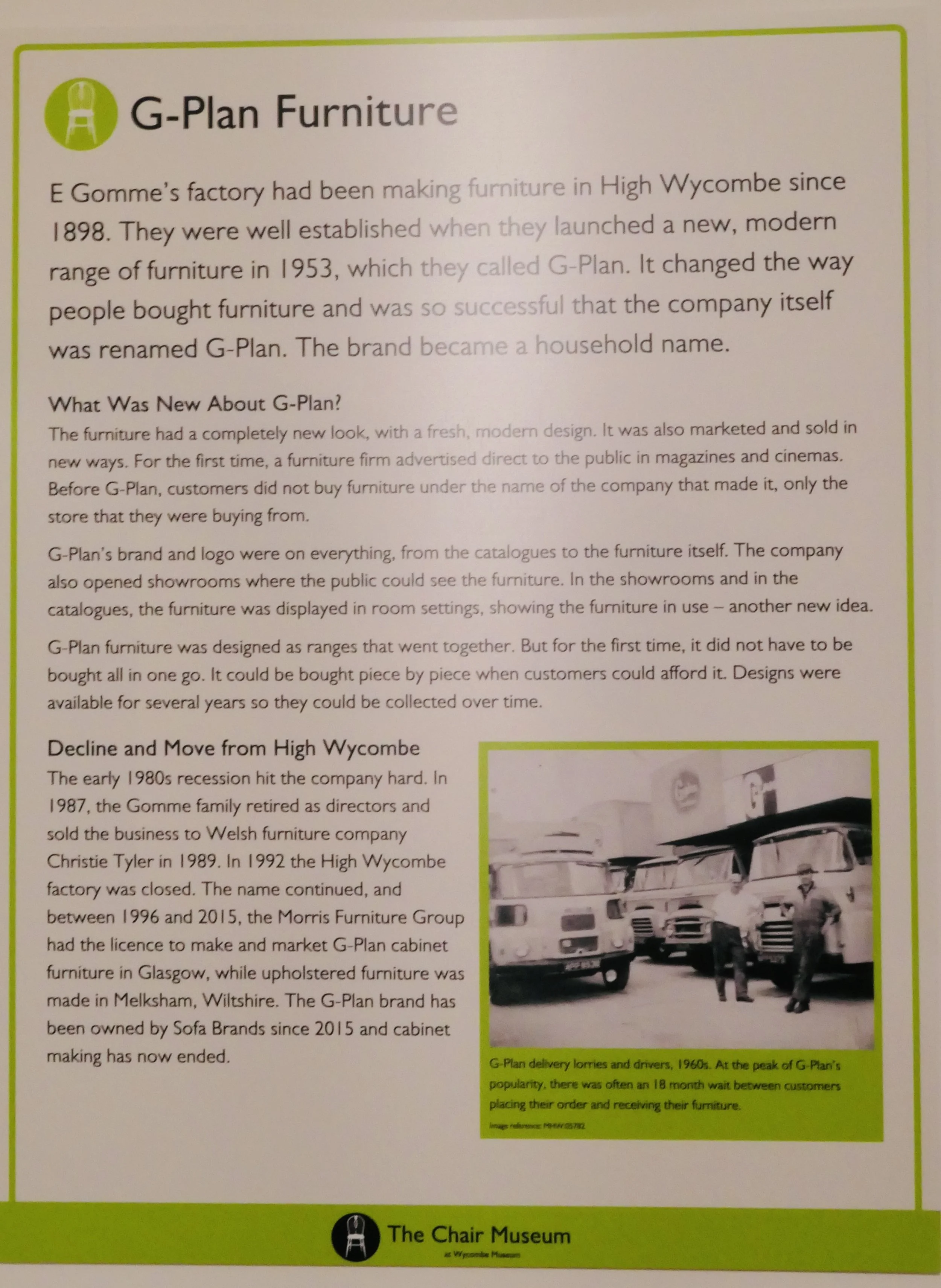

The digitised archive provided access to drawings and catalogues from G-Plan, Ercol and E. Gomme. Exploded views, tolerances, fixings — systems designed for repeatable manufacture and repair.

They offered structural clarity. What they lacked was atmosphere.

Technical drawings flatten labour and weight into information. For a practice positioned between furniture logic and architectural sensibility, that absence mattered.

Looking Beyond the Archive

To counter that flatness, I widened the research.

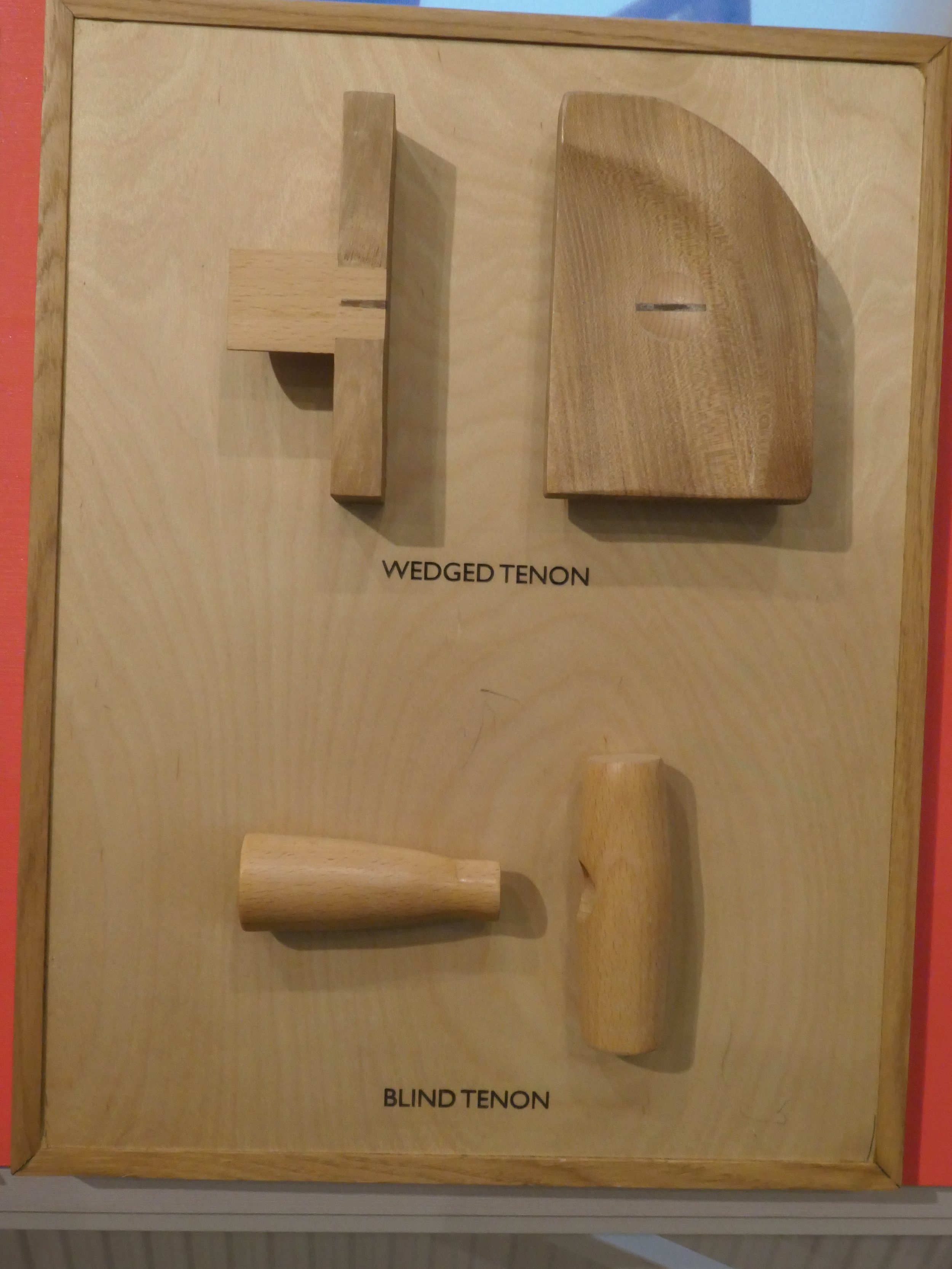

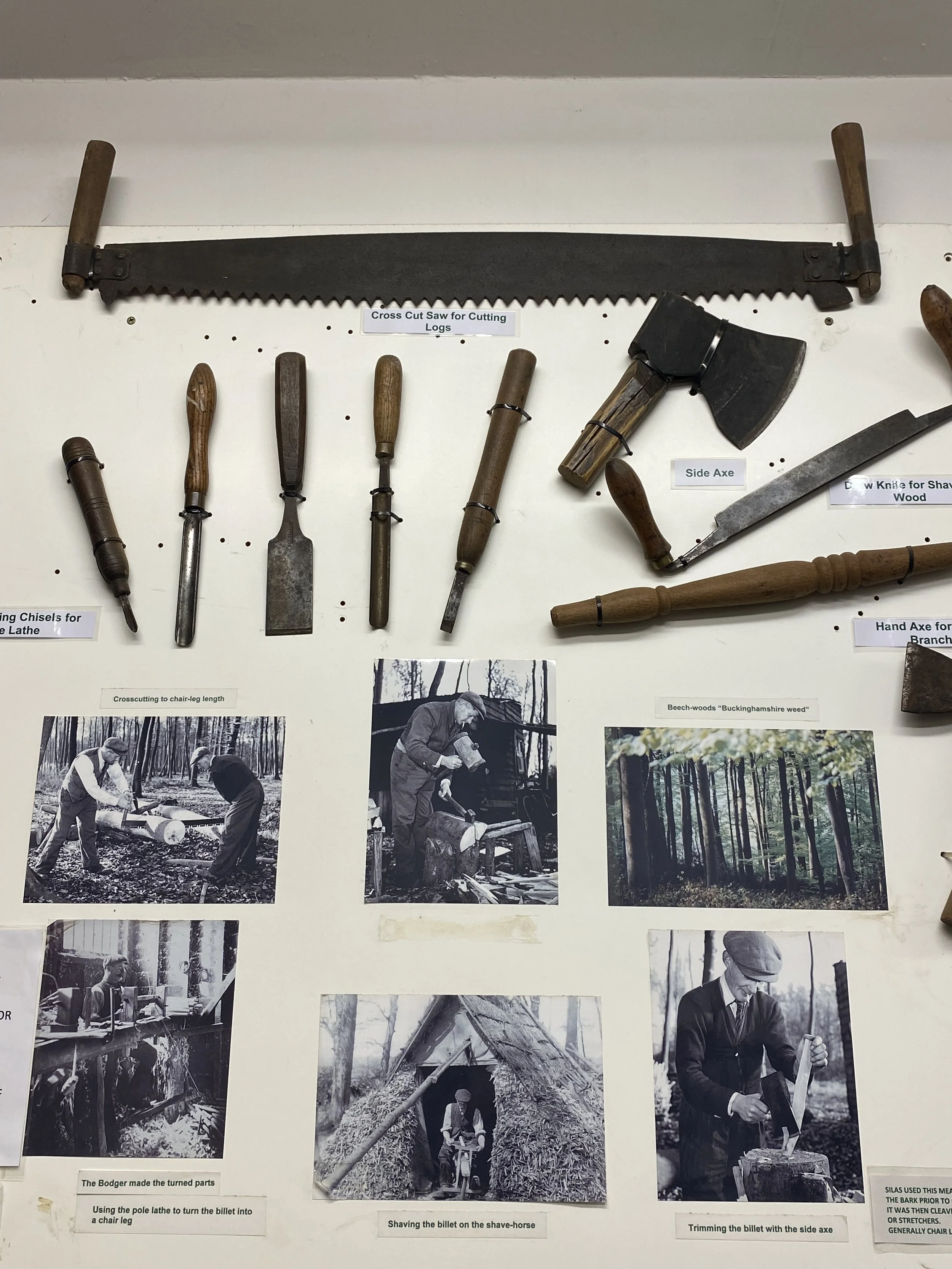

At High Wycombe Museum, I studied chairs directly — how joints resolve corners, carry stress and sit in space. At the Chair Making Museum at Kraftinwood, a conversation with Robert grounded the research in lived knowledge: production constraints, workshop pragmatics, the relationship between hand, tool and jig.

Joinery is never neutral. It is shaped by time, cost and material availability. Those constraints remain visible in the object.

Atmosphere, Architecture and Material Presence

The archive provided structural logic. It did not provide scale.

My sculptural forms are rooted in architectural shadow — particularly the mass and spatial restraint of the Barbican Centre, which has informed my thinking since first visiting in 1983. Its concrete surfaces, deep recesses and controlled light continue to shape how I construct form.

This project asks a specific question:

can furniture-scale joinery convincingly support architectural weight?

The joints I am developing are not replicas of historical systems. They are translations — domestic structural intelligence inserted into forms derived from architectural mass.

Furniture joinery evolved around repair, economy and human scale. Brutalist architecture operates at civic scale, permanence and material gravity. Bringing these logics together introduces friction.

That friction is deliberate.

The aim is not to aestheticise architecture, nor to monumentalise furniture, but to test whether modular joinery can hold forms that carry architectural presence.

Photographs: Labour and Shadow

Photographs played a key role in connecting these strands of research. Archival images of Wycombe furniture factories — particularly production-line scenes and joint-testing demonstrations — revealed something absent from diagrams: the physicality of making. Hands, bodies and materials under stress foreground labour in ways that directly inform how visible I want construction to be in my own work.

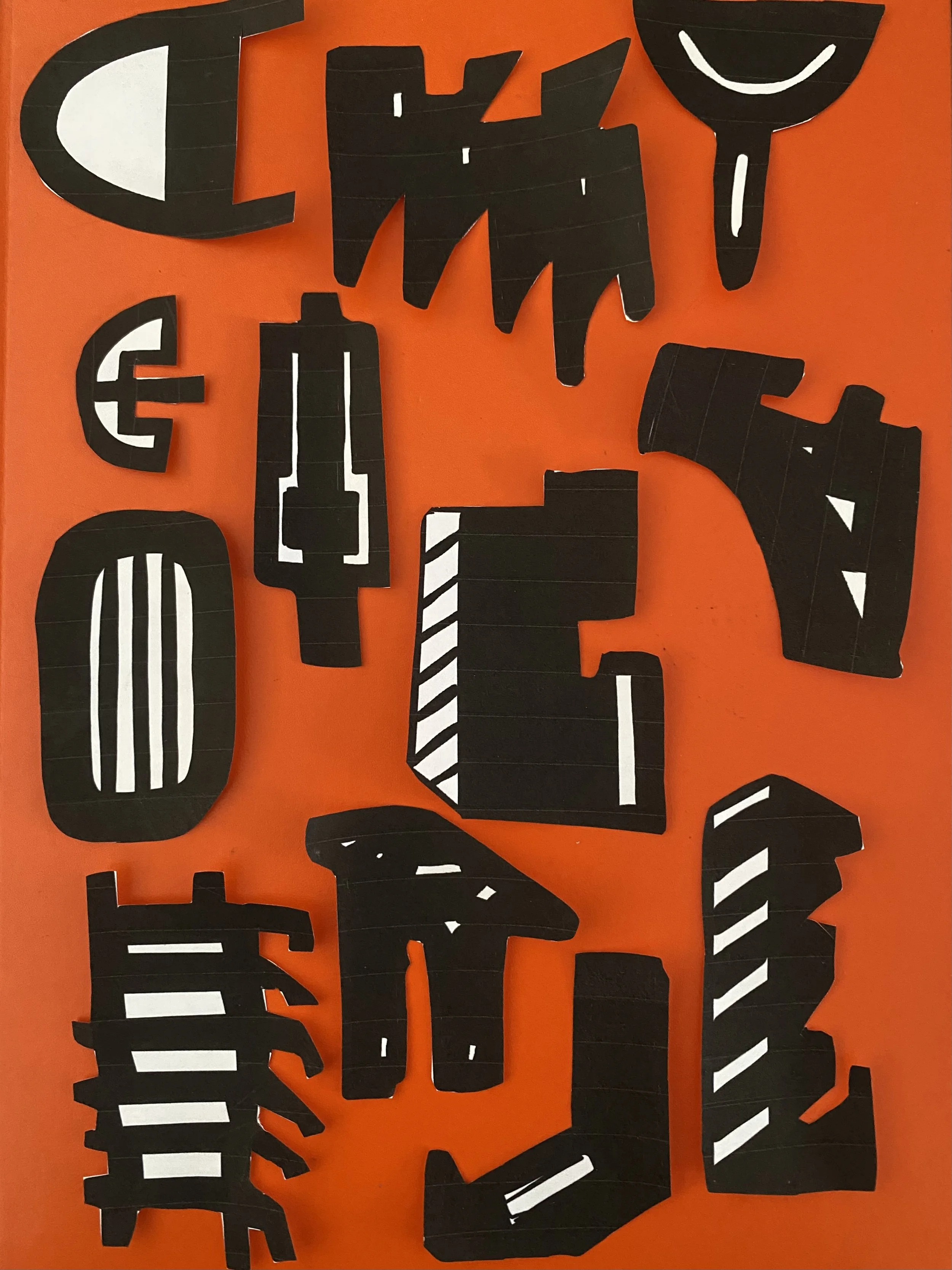

Alongside this, I revisited my own photographic archive of architectural shadows from The Barbican Centre and drew out key shadow shapes. These images are central to my sculptural thinking and remind me why modular systems matter to my practice. By bringing this sensibility into dialogue with furniture joinery research, I am asking how two languages — architectural shadow and furniture structure — might intersect.

Colour as Context

Colour required restraint. Jesmonite pigment can easily overpower form.

Revisiting mid-century palettes — ochres, muted greens, soft neutrals — provided reference points without becoming prescriptive. Colour needed to support structure, not distract from it.

What This Stage Established

This phase was not accumulation for its own sake. It situated the project within a system of values: how objects are made, how labour is revealed and how work occupies space.

It clarified what the joins must communicate:

structural intelligence

clarity of form

sensitivity to material behaviour

alignment with mid-century and Modernist principles

atmospheric presence

With this groundwork in place, the project could move from research into design — where translation, distortion and risk begin. The architectural sensibility informs the tone of the work — restraint, mass, shadow — rather than dictating the join geometry itself.