Casting as Translation: Jesmonite, Concrete and Surface Behaviour

Casting is where intention meets consequence.

Until now, the project evolved through research, drawing, cutting and mould-making. Casting introduced gravity, cure time and surface behaviour. The joins were no longer diagrams or prototypes. They had to perform.

This stage focused on casting selected designs in Jesmonite and concrete — not to produce finished works, but to test how each material translated form and structural intent.

From Mould to Object

Using the developed silicone moulds, I cast small join components with an emphasis on repeatability rather than isolated success.

Jesmonite captured detail and integrated colour precisely, but it exposed mould weaknesses immediately. Air bubbles, seam lines and inconsistencies became evidence of strain in the system.

Concrete shifted the dynamic. Its slower cure and greater mass altered both perception and handling. Edges softened. Light absorbed differently. The join’s authority changed under weight.

Surface Is Not Secondary

Surface behaviour became central. Sanding and polishing quickly demonstrated how overworking could strip a join of its architectural presence.

Jesmonite rewards restraint. Excess intervention introduces decoration. Concrete resists refinement differently; its grain and irregularity demand acceptance rather than control.

The goal was not uniformity across materials, but coherence.

Weight, Handling and Trust

Casting made weight unavoidable. The joins that struggled under weight were almost always the more complex geometries. Additional planes, recesses or layered elements that felt sophisticated in drawing introduced imbalance once cast. Mass exposed unnecessary decisions.

Repeated assembly exposed further issues: edge wear, small chips, subtle instability. These were not flaws but indicators of durability.

A join must hold.

It must also endure handling without becoming fragile.

What Translation Revealed

Casting translated earlier designs — sometimes faithfully, sometimes harshly.

It clarified:

which geometries survive across materials

how surface alters perceived strength

where weight strengthens or weakens intent

which joins remain viable beyond a single successful cast

The simpler geometries translated more convincingly. Overcomplicated joins lost authority under mass, revealing that clarity carries weight better than intricacy.

Preparing for Force

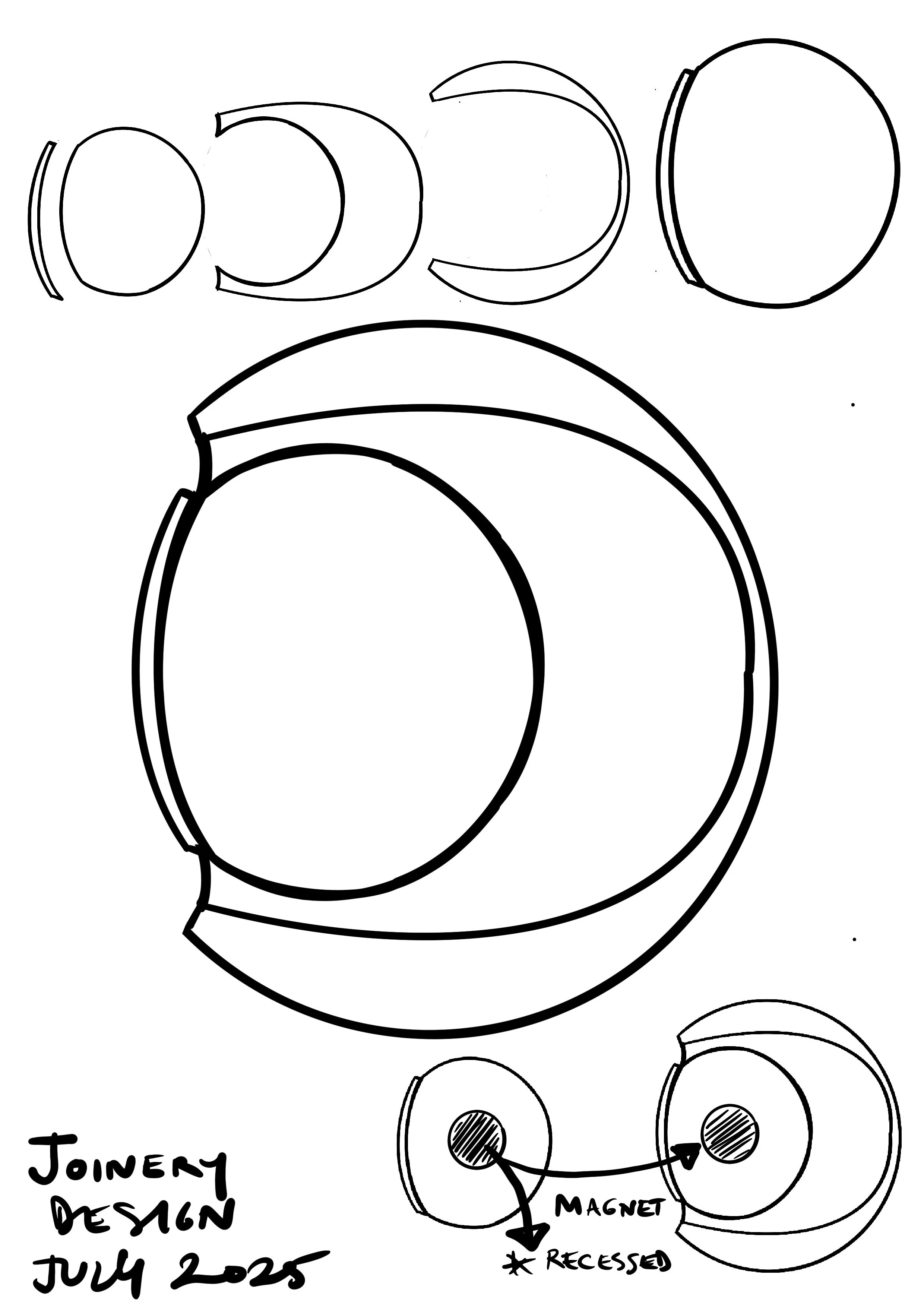

By the end of this stage, the joins existed as real objects with mass, surface and presence. They were ready to be tested not just as forms, but as systems — particularly once magnets were embedded and force became an active component.

Casting had given the joins a body. The next stage would ask whether that body could be trusted.